From the 1960s onwards, one of the most influential British literary commentators on science fiction was the novelist and critic Kingsley Amis. Best known for his novel

Lucky Jim, Amis was particularly fond of the social satire strand of SF as exemplified by Pohl and Kornbluth. Amis delivered a series of lectures on science fiction while working in the US, and these were published in 1960 as

New Maps of Hell, a book which did much to help contemporary science fiction regain a level of respectability which it had largely lost thanks to the garish pulp magazines and monstrous giant ant movies of the '50s.

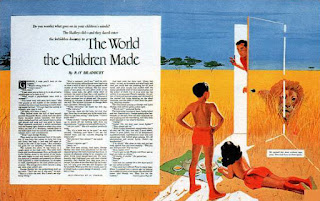

In 1963, Amis was tasked with reviewing Bradbury's

Something Wicked This Way Comes, recently released in a first edition from Ruper Hart-Davis (pictured, left), for the

Observer newspaper. The review appeared on 24 February 1963.

Unfortunately,

Something Wicked did not strike the right note with Amis. After outlining what he saw as the difference between science fiction and fantasy - the one built on logic and extrapolation, the other built on "whimsy" - he turned to an assessment of Bradbury. "Except at his very best (in

Fahrenheit 451, for instance), he has always tended to overwrite, to load every rift not with ore but with pyrites", he writes, implying that Bradbury is already past his best. This assessment seems to have become accepted wisdom in the UK from around this time.

Amis then summarises the plot of the novel. He finds most of Bradbury's plot choices to be largely arbitrary or unmotivated:

A carnival turns up from somewhere under the management of Mr Dark, who is death or the devil or somebody. He operates a carousel which adds to or subtracts from your age somehow, so that a small boy becomes 200 years old and his aunt regresses to childhood. A freak show includes a Fat Man who grew fat through lusting too much or something, and an ex-lightning-rod salesman squashed into dwarfism because he was really a small man in some way. There is a witch, halfheartedly modernised, who travels by balloon instead of broomstick.

The review is amusing, but doesn't admit of any possibility of symbolism or magic as organising principles in a fantasy story, and suggest a reviewer who is hostile to the genre as much as he is hostile to the work under review.

As for the science fiction genre, in 1981 SF writer J.G.Ballard reviewed an anthology Amis had newly compiled, entitled

The Golden Age of Science Fiction. In the twenty-odd years since

New Maps of Hell, according to Ballard, Amis had shifted from a position of championing the genre of SF to being quite hostile to much of it. You can read Ballard's pithy and perceptive comments

here.