Wednesday, December 25, 2013

Ray Bradbury's Christmas Gift

Seasons greetings, everyone!

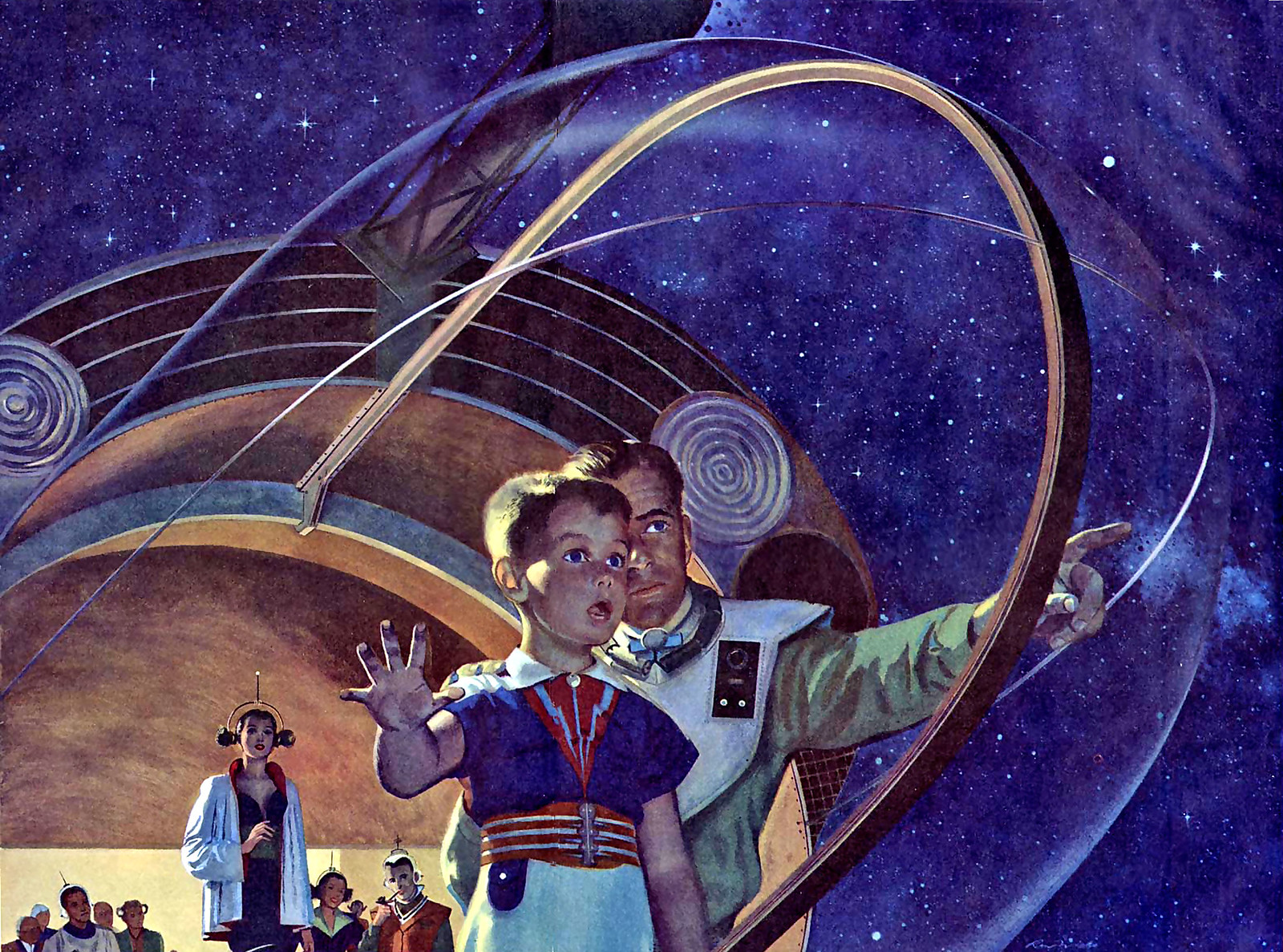

I've noted previously that Ray Bradbury wrote very few Christmas-themed stories, but one of his best-known is "The Gift". It was first published in Esquire magazine in 1952. The artwork above (click to embiggen) is by Ren Wickes, and in the child's face beautifully captures the good old "sense of wonder" people used to talk about in science fiction stories.

To find out why the child is so astonished, read "The Gift" here.

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Signed by Ray

Given that Ray Bradbury spent so many hours signing books, some people say that an unsigned Bradbury is worth more than a signed one. I've never been into collecting signed items, but I do have a few things signed by Ray. Here's a couple of them:

The typical Bradbury declaration "Onward!" on a paperback copy of The Cat's Pajamas. And a simple "Love!" on a postcard from one of his stage plays. It was partly because of this card that I knew the name Alan Neal Hubbs. When I met Alan a few years later, he was astonished that anyone from the UK had ever heard of him.

Somewhere, I believe I have another signed item, where Ray wrote one of his other declarations, the odd "Mad love!" - which I have always assumed was inspired by the Peter Lorre film.

The typical Bradbury declaration "Onward!" on a paperback copy of The Cat's Pajamas. And a simple "Love!" on a postcard from one of his stage plays. It was partly because of this card that I knew the name Alan Neal Hubbs. When I met Alan a few years later, he was astonished that anyone from the UK had ever heard of him.

Somewhere, I believe I have another signed item, where Ray wrote one of his other declarations, the odd "Mad love!" - which I have always assumed was inspired by the Peter Lorre film.

Friday, December 20, 2013

Fight!

As Harry Hill might say:

Now, I like Ray Bradbury. And I like Alfred Hitchcock. But which is better? There's only one way to find out: fight!

That seems to be the concept behind issue 45 of the periodical McSweeney's. The explanation behind it all is, apparently, that this issue reprints various stories taken from short story anthologies edited by Bradbury and Hitchcock.

In Bradbury's long career, he only ever edited two published anthologies: Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow (1952) and The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories (1956).

And in his long career, Hitchcock edited... probably no books at all. He was named as editor on a lengthy series of paperback anthologies, with titles such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents Stories My Mother Never Told Me, but it is almost certain that these were ghost-edited by others. Robert Arthur was responsible for the first ones, and other ghosts probably followed in his footsteps. There's a running thread on this topic, with lots of cover photos, here.

So which is better? A Bradbury anthology or a Hitchcock anthology? Buy McSweeney's 45 to find out...

Now, I like Ray Bradbury. And I like Alfred Hitchcock. But which is better? There's only one way to find out: fight!

That seems to be the concept behind issue 45 of the periodical McSweeney's. The explanation behind it all is, apparently, that this issue reprints various stories taken from short story anthologies edited by Bradbury and Hitchcock.

In Bradbury's long career, he only ever edited two published anthologies: Timeless Stories for Today and Tomorrow (1952) and The Circus of Dr Lao and Other Improbable Stories (1956).

And in his long career, Hitchcock edited... probably no books at all. He was named as editor on a lengthy series of paperback anthologies, with titles such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents Stories My Mother Never Told Me, but it is almost certain that these were ghost-edited by others. Robert Arthur was responsible for the first ones, and other ghosts probably followed in his footsteps. There's a running thread on this topic, with lots of cover photos, here.

So which is better? A Bradbury anthology or a Hitchcock anthology? Buy McSweeney's 45 to find out...

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Exclusive! Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury Volume 2

Yes, it's a world exclusive: I can now reveal the contents of the second volume of The Collected Stories of Ray Bradbury: a Critical Edition, Volume 2: 1943-1944. The book is due for release from Kent State University Press in September 2014, and seems to already be available for pre-order from the publisher, here.

Attentive readers may have noticed that this second volume covers a much smaller time period than Volume 1, which spanned the period 1938-1943. This effectively reflects the accelerating pace of Bradbury's career as a professional writer, not necessarily writing more than previously, but getting more work published.

Without any further ado, here's the list of stories for Volume 2, courtesy of the book's editor, Jon Eller from the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies:

** These stories have never been published in a book; their only previous appearances were in their first magazine publication.

*** Only previously available within a limited edition volume from Subterranean Press.

The Collected Stories series was initiated by Bill Touponce and Jon Eller, with Bill as General Editor and Jon as Textual Editor. Now that Bill has retired (but still working on independent projects such as his recent book on Lovecraft, Dunsany and Bradbury), Jon has taken on all the editorial duties himself, supported by a small team of editorial associates at Indiana University's Institute for American Thought, and a couple of consulting editors: Donn Albright and a certain Phil Nichols.

Since the aim of the Collected Stories series is to establish Bradbury's versions of the texts - rather than versions modified by a magazine editor - Bradbury's own preferred titles are being used here wherever there is primary or secondary evidence to support it. So, for example, "Doodad" has it's original title "Everything Instead of Something" restored.

It's not just the titles: Collected Stories aims to identify Bradbury's intentions for each text, and this means going back to the author's own manuscripts where possible. In this instance, Jon is using original Bradbury typescripts for three stories ("The Shape of Things", "The Man Upstairs", and "Where Everything Ends"), and original opening pages for nine others. Of these, Jon reports "We have first-page carbons that Ray appears to have saved as proof of date and authorship while stories circulated during the war years." Through this documentary research, the editorial team is able to not only retrieve otherwise forgotten story titles, but in some cases to also retain Bradbury's preferred spellings and compounds and reject the house-styled changes imposed by various pulp magazine editors.

Another aim of the series is to establish the chronology of composition, which previously was somewhat shrouded in mystery. There are at least two reasons for this. First, Bradbury's stories might circulate for a number of years before being chosen for publication by a magazine editor, and so we have a situation where a story might be written in 1943, but not be published until 1947. And second, most of us are familiar with the stories from their appearance in Bradbury's books, giving us the mistaken impression that stories published side-by-side are of a similar vintage - leading many a critic to draw invalid conclusions about Bradbury's authorship. The stories collected in Volume 2 span a compositional period from April 1943 to March 1944, one year of professional output.

For scholars, this volume will once again offer a new insight into Bradbury's developing professional authorship, and make plain his evolving ideas by showing those ideas in chronological order. For the general Bradbury reader, it will offer a chance to enjoy a number of previously rare and obscure tales. September 2014 is a long way off, but the wait will be worth it!

Attentive readers may have noticed that this second volume covers a much smaller time period than Volume 1, which spanned the period 1938-1943. This effectively reflects the accelerating pace of Bradbury's career as a professional writer, not necessarily writing more than previously, but getting more work published.

Without any further ado, here's the list of stories for Volume 2, courtesy of the book's editor, Jon Eller from the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies:

- The Sea Shell

- Everything Instead of Something (Doodad)*

- The Ducker*

- The Shape of Things (Tomorrow's Child)

- The Night

- Perchance to Dream (Asleep in Armageddon)

- Referent

- The Calculator (Jonah of the Jove Run)**

- The Emissary

- And Watch the Fountains**

- The Million Year Picnic

- The Man Upstairs

- Reunion

- Autopsy (Killer, Come Back to Me!)**

- The Long Night

- Lazarus Come Forth**

- There Was an Old Woman

- The Trunk Lady

- Jack-in-the-Box

- Where Everything Ends***

- Bang! You're Dead!

- Enter-the Douser (Half-Pint Homicide)

- Rocket Skin**

- Forgotten Man (It Burns Me Up!)

- The Jar

** These stories have never been published in a book; their only previous appearances were in their first magazine publication.

*** Only previously available within a limited edition volume from Subterranean Press.

The Collected Stories series was initiated by Bill Touponce and Jon Eller, with Bill as General Editor and Jon as Textual Editor. Now that Bill has retired (but still working on independent projects such as his recent book on Lovecraft, Dunsany and Bradbury), Jon has taken on all the editorial duties himself, supported by a small team of editorial associates at Indiana University's Institute for American Thought, and a couple of consulting editors: Donn Albright and a certain Phil Nichols.

Since the aim of the Collected Stories series is to establish Bradbury's versions of the texts - rather than versions modified by a magazine editor - Bradbury's own preferred titles are being used here wherever there is primary or secondary evidence to support it. So, for example, "Doodad" has it's original title "Everything Instead of Something" restored.

It's not just the titles: Collected Stories aims to identify Bradbury's intentions for each text, and this means going back to the author's own manuscripts where possible. In this instance, Jon is using original Bradbury typescripts for three stories ("The Shape of Things", "The Man Upstairs", and "Where Everything Ends"), and original opening pages for nine others. Of these, Jon reports "We have first-page carbons that Ray appears to have saved as proof of date and authorship while stories circulated during the war years." Through this documentary research, the editorial team is able to not only retrieve otherwise forgotten story titles, but in some cases to also retain Bradbury's preferred spellings and compounds and reject the house-styled changes imposed by various pulp magazine editors.

Another aim of the series is to establish the chronology of composition, which previously was somewhat shrouded in mystery. There are at least two reasons for this. First, Bradbury's stories might circulate for a number of years before being chosen for publication by a magazine editor, and so we have a situation where a story might be written in 1943, but not be published until 1947. And second, most of us are familiar with the stories from their appearance in Bradbury's books, giving us the mistaken impression that stories published side-by-side are of a similar vintage - leading many a critic to draw invalid conclusions about Bradbury's authorship. The stories collected in Volume 2 span a compositional period from April 1943 to March 1944, one year of professional output.

For scholars, this volume will once again offer a new insight into Bradbury's developing professional authorship, and make plain his evolving ideas by showing those ideas in chronological order. For the general Bradbury reader, it will offer a chance to enjoy a number of previously rare and obscure tales. September 2014 is a long way off, but the wait will be worth it!

Tuesday, November 05, 2013

Destination: Planet Negro!

Destination: Planet Negro! is a low-budget American independent film from writer-director-actor Kevin Willmott. Out of the mainstream of commercial distribution, this satirical comedy is picking up some good reviews and festival commendations. It's politically incorrect in many places, but its social and political heart is in the right place: it uses an affectionate parody of early science fiction films to rapidly get to a smart but uncomfortable analysis of American politics of race.

The reason for this review on Bradburymedia? The premise of the film (but only the premise) coincides almost exactly with Ray Bradbury's assessment of "the Negro problem" (as it was then sometimes called) in his 1950 story "Way in the Middle of the Air", first published as a chapter of The Martian Chronicles.

In Bradbury's story, African-Americans have had enough, and spontaneously decide en masse that they are going to leave the Earth, and start again on Mars. Even at the time of publication, the story presented an unlikely scenario, but it allowed Bradbury to make some sharp points about the mistreatment of minorities, and some sections of the white population's inability to get over the idea of equality. Bradbury was aware of the difficult politics he was dealing with, and equally aware of the artificiality of the story. With the passage of time, and in particular the growth of the Civil Rights movement, "Way in the Middle of the Air" appeared dated, leading Bradbury to remove it from later reprintings of The Martian Chronicles. The story remained available as an isolated short story, but the author considered it no longer sustainable in a supposedly futuristic SF novel.

A similar logic motivates the black intelligentsia of the year 1939 at the start of Destination: Planet Negro! as they reluctantly agree that starting again elsewhere is the only solution to the "Negro problem". But where to go? Surely not to Africa, nor to the North or South Poles, nor to Europe. No, the solution is Mars. What convinces them is the expertise of Dr Warrington Avery (played by Willmott), backed up by a delightfully sprightly and potty-mouthed George Washington Carver. Carver's earlier liaison with Wernher von Braun and Robert Goddard has led to the development of a super-rocket, built on technology derived from peanuts and sweet potatoes ("What that man can't do with peanuts", says one observer).

And so begins a film which looks for all the world like a fairly mindless comedy. Shot in black and white to resemble a contemporary science-fiction film, with a spaceship crew made up of Dr Avery, his beautiful and highly intelligent astronomer daughter, and barnstorming pilot Race ("Call me Ace"), it has some good sight gags and verbal wit. Oh, and a robot which George Washington Carver has programmed to sound like his master from slavery days. Like I said, political correctness is not a concern of this film!

Of course, trouble arises, and the ship is accidentally propelled not to Mars, but to some mysterious other world. At this point, the film goes to full colour, Wizard of Oz style. As our heroes explore this world, they discover it has some remarkable similarities to Earth. Humanoids. Speaking English (and Spanish). And indications of slavery. They get their first clue about the slavery when they are forced to ride with some Spanish-speaking migrant workers. "On our planet," observes Dr Avery, "they would be considered... Mexicans."

Dr Avery's theorising takes a slightly Bradburyan turn - echoes of Fahrenheit 451 in this case - when he observes that some of the natives have little wires running to their ears, which cause them to vibrate and gyrate. The wires are connected to "little typewriters." Clearly, a mechanism by which their overseers control them. Most disturbing of all: some of the slaves are obviously malnourished, and barely have the strength to hold up their pants.

Of course, they're on present-day Earth. Far from having travelled to a distant place, they have travelled through time. And here, while the humour continues, the film shows its true, Jonathan Swift-like technique: this is a pointed political satire, dressed up as comic fantasy. Our heroes learn about the Civil Rights movement, and how it brought about change - ultimately, a black president, black heroes of popular culture - but somehow still made little difference. Temporarily locked in jail, Dr Avery observes that all of his fellow prisoners are non-white. Segregation has ended?

Dr Avery explores modern day Kansas - another Oz reference, but Willmott also hails from Kansas. Accompanying Karen Wilborn, a professor of black studies, he is able to sum up with sadness what she teaches him about segregation and integration:

"So we integrated with them, but they... didn't integrate with us."

The film confronts head-on the apparent paradox of twenty-first-century American race politics: the biggest American heroes of movies, music, sport and politics may be black; but at the same time, the prison population is predominantly black. It also, by way of a subplot, head-on addresses homophobia and its apparent persistence in American black culture, and indeed has a gay character ultimately saving the world through safe sex and a time-paradox plot to kill Hitler. (It's hard to explain. You'll have to watch the film.)

As a low-budget film, it occasionally struggles with technical problems, such as the odd quirk in the soundtrack, but surprisingly the SF stuff - rocketships, meteors, black holes - is done well, in its "Buster Crabbe, Flash in the pan" way, to paraphrase one of the characters.

To be honest, as a white Englishman, I can't imagine that I am the intended audience for this film, and I'm sure its true audience will appreciate it even more than I do. But whether you enjoy it for the SF spoofiness, the politics, George Washington Carver saying "motherf***er", or a 1930s barnstormer learning to do a twenty-first-century urban walk, enjoy it you probably will.

I don't know when, or even if, you will get a chance to see this film, but you can follow it on its Facebook page, and perhaps catch a screening at a film festival some time. Don't be put off by its illusion of Flash Gordon or Conquest of Space datedness, or its slightly slow and talky opening. It's a witty and well constructed story, played by some excellent actors, just done on a low budget. I want to see more from Kevin Wilmott, evidently a clever satirist.

This is one of two films to come out this year with a premise that sounds like a Bradbury story (the other one is Gravity, whose premise sounds like the short story "Kaleidoscope"). Beyond the premise, though, I can safely say that this is not Bradbury. But it does have a satiric edge and a plea for diversity which Ray might approve of.

The reason for this review on Bradburymedia? The premise of the film (but only the premise) coincides almost exactly with Ray Bradbury's assessment of "the Negro problem" (as it was then sometimes called) in his 1950 story "Way in the Middle of the Air", first published as a chapter of The Martian Chronicles.

In Bradbury's story, African-Americans have had enough, and spontaneously decide en masse that they are going to leave the Earth, and start again on Mars. Even at the time of publication, the story presented an unlikely scenario, but it allowed Bradbury to make some sharp points about the mistreatment of minorities, and some sections of the white population's inability to get over the idea of equality. Bradbury was aware of the difficult politics he was dealing with, and equally aware of the artificiality of the story. With the passage of time, and in particular the growth of the Civil Rights movement, "Way in the Middle of the Air" appeared dated, leading Bradbury to remove it from later reprintings of The Martian Chronicles. The story remained available as an isolated short story, but the author considered it no longer sustainable in a supposedly futuristic SF novel.

|

| Destination: Mars. Turn left at the asteroid belt. |

A similar logic motivates the black intelligentsia of the year 1939 at the start of Destination: Planet Negro! as they reluctantly agree that starting again elsewhere is the only solution to the "Negro problem". But where to go? Surely not to Africa, nor to the North or South Poles, nor to Europe. No, the solution is Mars. What convinces them is the expertise of Dr Warrington Avery (played by Willmott), backed up by a delightfully sprightly and potty-mouthed George Washington Carver. Carver's earlier liaison with Wernher von Braun and Robert Goddard has led to the development of a super-rocket, built on technology derived from peanuts and sweet potatoes ("What that man can't do with peanuts", says one observer).

|

| Intrepid heroes: Tosin Morohunfola, Danielle Cooper, Kevin Willmott. |

And so begins a film which looks for all the world like a fairly mindless comedy. Shot in black and white to resemble a contemporary science-fiction film, with a spaceship crew made up of Dr Avery, his beautiful and highly intelligent astronomer daughter, and barnstorming pilot Race ("Call me Ace"), it has some good sight gags and verbal wit. Oh, and a robot which George Washington Carver has programmed to sound like his master from slavery days. Like I said, political correctness is not a concern of this film!

Of course, trouble arises, and the ship is accidentally propelled not to Mars, but to some mysterious other world. At this point, the film goes to full colour, Wizard of Oz style. As our heroes explore this world, they discover it has some remarkable similarities to Earth. Humanoids. Speaking English (and Spanish). And indications of slavery. They get their first clue about the slavery when they are forced to ride with some Spanish-speaking migrant workers. "On our planet," observes Dr Avery, "they would be considered... Mexicans."

Dr Avery's theorising takes a slightly Bradburyan turn - echoes of Fahrenheit 451 in this case - when he observes that some of the natives have little wires running to their ears, which cause them to vibrate and gyrate. The wires are connected to "little typewriters." Clearly, a mechanism by which their overseers control them. Most disturbing of all: some of the slaves are obviously malnourished, and barely have the strength to hold up their pants.

|

| Enslaved by the wires and the little typewriter. |

Of course, they're on present-day Earth. Far from having travelled to a distant place, they have travelled through time. And here, while the humour continues, the film shows its true, Jonathan Swift-like technique: this is a pointed political satire, dressed up as comic fantasy. Our heroes learn about the Civil Rights movement, and how it brought about change - ultimately, a black president, black heroes of popular culture - but somehow still made little difference. Temporarily locked in jail, Dr Avery observes that all of his fellow prisoners are non-white. Segregation has ended?

Dr Avery explores modern day Kansas - another Oz reference, but Willmott also hails from Kansas. Accompanying Karen Wilborn, a professor of black studies, he is able to sum up with sadness what she teaches him about segregation and integration:

"So we integrated with them, but they... didn't integrate with us."

|

| Twenty-first-century malnutrition: not even the strength to pull up their pants. |

The film confronts head-on the apparent paradox of twenty-first-century American race politics: the biggest American heroes of movies, music, sport and politics may be black; but at the same time, the prison population is predominantly black. It also, by way of a subplot, head-on addresses homophobia and its apparent persistence in American black culture, and indeed has a gay character ultimately saving the world through safe sex and a time-paradox plot to kill Hitler. (It's hard to explain. You'll have to watch the film.)

As a low-budget film, it occasionally struggles with technical problems, such as the odd quirk in the soundtrack, but surprisingly the SF stuff - rocketships, meteors, black holes - is done well, in its "Buster Crabbe, Flash in the pan" way, to paraphrase one of the characters.

To be honest, as a white Englishman, I can't imagine that I am the intended audience for this film, and I'm sure its true audience will appreciate it even more than I do. But whether you enjoy it for the SF spoofiness, the politics, George Washington Carver saying "motherf***er", or a 1930s barnstormer learning to do a twenty-first-century urban walk, enjoy it you probably will.

|

| Learning to walk the walk. |

I don't know when, or even if, you will get a chance to see this film, but you can follow it on its Facebook page, and perhaps catch a screening at a film festival some time. Don't be put off by its illusion of Flash Gordon or Conquest of Space datedness, or its slightly slow and talky opening. It's a witty and well constructed story, played by some excellent actors, just done on a low budget. I want to see more from Kevin Wilmott, evidently a clever satirist.

|

| As we remember him today? George Washington Carver. What that man can't do with peanuts. |

This is one of two films to come out this year with a premise that sounds like a Bradbury story (the other one is Gravity, whose premise sounds like the short story "Kaleidoscope"). Beyond the premise, though, I can safely say that this is not Bradbury. But it does have a satiric edge and a plea for diversity which Ray might approve of.

Saturday, November 02, 2013

Searching for Ray Bradbury

Earlier this year Blüroof Press released Searching for Ray Bradbury: Writings about the Writer and the Man by Steven Paul Leiva, a collection of essays written during Bradbury's final years and since his death in 2012. Novelist Leiva was central to several tributes to Bradbury in Los Angeles, and it is thanks to his efforts that the city officially celebrated Bradbury's ninetieth birthday with Ray Bradbury Week in 2010, named Ray Bradbury Square next to the Los Angeles Public Library, and recently dedicated the Palms-Rancho Branch Library in Bradbury's name.

Searching for Ray Bradbury reads as a personal journey, revealing something of what made Bradbury a significant figure in American literature and Los Angeles' civic affairs. It also, in a way, is a search for Steven Paul Leiva, addressing the question: who is this fellow who has helped bring Bradbury the recognition he deserves?

Let me first say that this isn't the kind of book to tell you a great deal about Bradbury - for that, you need a biography like Weller's The Bradbury Chronicles, or a literary biography like Eller's Becoming Ray Bradbury. But Searching for Ray Bradbury does give a unique view of a moment of transition, where celebration of Bradbury's longevity necessarily gave way to memorialising.

The slim volume (just under ninety pages) is best seen as a thick chapbook rather than an undersized paperback, and is modestly priced at $5.39 on Amazon, but is also available for Kindle at $1.99. I have read only the print version, but I understand that the Kindle version omits the photographs found in the print version.

The book's cover is a reproduction of Lou Romano's affectionate caricature of Ray Bradbury, originally created for the Writers' Guild magazine Written By (you can read Romano's own fascinating account of the creation of this piece on his own blog, here.) The foreword is written by SF writer and futurist David Brin, who gives his appreciation of Bradbury's ability to both explore the darkness of the human heart and promote a optimistic vision of humankind's future beyond the Earth, an idea which Leiva also picks up on in one of the essays. Brin describes Leiva's book as a "personal and deeply moving tribute" which shines a loving light upon some little known aspects of this intricate and deeply passionate man".

So what of the essays contained here? They were all originally published elsewhere - some of them on Leiva's own blog This 'n' That, others in places such as Written By, KCET.org and The Huffington Post. While each one was written for a different, specific purpose, collecting them together here allows us to see a broader picture. Articles which were illuminating celebrations with Bradbury in life are now joined with items which to some extent eulogise the late author. It's great to see the pictures of Bradbury and Leiva triumphantly enjoying the dedication of Ray Bradbury Week, and quite poignant to then see the photos of the tributes a couple of years on, after Ray's passing.

The first essay, "Searching for Ray Bradbury," originally appeared in an L.A.Times blog,and attempts to give an account of what Ray Bradbury is, and where such an individual comes from. Leiva addresses what most people (think they) know about Bradbury: science fiction, and small-town America. He could have presented this essay as biography, but he chooses instead to take a Bradburyan turn and address it through metaphor:

The second essay, "Ray Bradbury Week in Los Angeles," explains how the previous essay led directly to Leiva's creation of Ray Bradbury Week, a week-long celebration of Bradbury's life and work, timed to coincide with Bradbury's ninetieth birthday on 22 August 2010. I was fortunate enough to get to L.A. around the time of these events, and attended Ray's public birthday party, held in Glendale's wonderful Mystery & Imagination bookshop. I had to leave before the official week began, but the party gave me an opportunity to briefly meet Steven Paul Leiva, and to see him MCing the open-mic tributes to Ray which ran throughout the afternoon. The essay on Ray Bradbury Week is surprisingly brief, and in the context of the book seems unduly modest for such a grand achievement. It's not every day that a major city dedicates itself unreservedly to the celebration of an author, and I can't help feeling that it was a lot more difficult to negotiate than Leiva allows us to believe in this chapter. Nevertheless, the photos in this section speak volumes, showing us Bradbury looking sometimes proud, sometimes awed, and occasionally overwhelmed by his adopted home's expression of affection. (It occurs to me that this chapter will lose some of its power in the Kindle edition, where the pictures have been removed.)

Essay three, "London to Los Angeles, Dickens to Bradbury: a Tale of Two Signs" sees Leiva on his first naive visit to London, literally stumbling in the dark as he tries to make sense of his new surroundings, and serendipitously spotting a sign linking a church to a Dickens novel. In parallel to this, he writes of driving around Venice, California, in search of the houses Bradbury had lived in when he first moved to the West Coast. Bradbury makes a brief appearance in this piece, a sad tale in which the old Bradbury house is demolished. Fortunately, a sign attached to the house, commemorating Bradbury's having written The Martian Chronicles there, turns up, and Leiva is the one to report this happy news to others who feared it had been lost along with the house itself. A somewhat rambling piece - how did we get from a flat in London to a demolished house in Venice, CA? - but an effortless one which begins to fulfill the book's title Searching for Ray Bradbury and in the process begins to reveal just a little of Leiva's background.

The third essay also introduces Jon Eller, the co-founder of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies, as a somewhat intrepid biographer, and essay number four follows directly on from this, being a review of Eller's book Becoming Ray Bradbury. It's a fine assessment of a fine book, bookended with a couple of anecdotes of Leiva's friendship with Bradbury.

My personal favourite of the essays collected here is chapter five, "Masterheart of Mars". Here Leiva explains how it was that Bradbury, that most non-technical of SF writers (if he even really was an SF writer; Leiva says he wasn't, and I tend to agree) came to be such an enormous inspiration to space scientists, to the extent that the team in charge of the Curiosity Mars rover decided to name the planetary explorer's base "Bradbury Landing" in 2012. Leiva puts it down to Bradbury's almost instinctive address of three aspects of the human condition which led him to advocate moving our species out to the planets, starting at Mars: we have an urge to survive, we have an urge to seek knowledge, and we have a difficult-to-define urge to not be hemmed in. This last is something that Leiva is ambivalent about, saying it is either incredibly primitive, or incredibly advanced. The resolution to that particular conundrum is probably to be found in Leiva's smart characterisation of Bradbury as "a romantic with a nineteenth century imagination combined with twentieth century anxieties", an assessment which successfully accounts for the yearning-yet-jaded view of humankind in The Martian Chronicles.

Essay six is a brief account of the creation of Ray Bradbury Square, a public space at Fifth and Flower in Los Angeles, right outside the public library that meant so much to Bradbury. Essay seven then continues the story with a detailed account of the dedication ceremony. As with the declaration of "Ray Bradbury Week" there is a sense of celebration, but this time with the tinge of sadness that Bradbury was not around to see the simple legend "Author - Angeleno" beneath his name.

Finally, essay eight tackles the title of the volume, and searches for the real Ray Bradbury. Here Leiva goes into the greatest detail about his own personal connection to Bradbury, which dates back to work they did together on a film adaptation of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland. Leiva points to a transition which had somehow occurred in Bradbury's career, where he slipped from being "just" an author with the near anonymity that so often accompanies authorship, to being a sought-after interviewee, public speaker and raconteur. Leiva almost suggests embarrassment at having, for a time, fallen into just seeing Ray as the the public persona. The essay shows how he re-connected with Bradbury the author through directing a staged reading of "The Better Part of Wisdom" in 2010.

Searching for Ray Bradbury is a brisk read, partly because it is a slim volume, but also because of Leiva's essay-writing skill. Because of his initiation of so many Bradbury tributes, there is a danger that this collection could place Leiva at the centre of events, and inadvertently become self-aggrandising. But what lifts the book above this is precisely the way he finds the object of his search: hidden in plain sight, right there in Bradbury the public persona, is Bradbury the humanitarian, Bradbury the author. Leiva finds the true Bradbury by connecting anew with Bradbury's text.

Searching for Ray Bradbury reads as a personal journey, revealing something of what made Bradbury a significant figure in American literature and Los Angeles' civic affairs. It also, in a way, is a search for Steven Paul Leiva, addressing the question: who is this fellow who has helped bring Bradbury the recognition he deserves?

Let me first say that this isn't the kind of book to tell you a great deal about Bradbury - for that, you need a biography like Weller's The Bradbury Chronicles, or a literary biography like Eller's Becoming Ray Bradbury. But Searching for Ray Bradbury does give a unique view of a moment of transition, where celebration of Bradbury's longevity necessarily gave way to memorialising.

The slim volume (just under ninety pages) is best seen as a thick chapbook rather than an undersized paperback, and is modestly priced at $5.39 on Amazon, but is also available for Kindle at $1.99. I have read only the print version, but I understand that the Kindle version omits the photographs found in the print version.

The book's cover is a reproduction of Lou Romano's affectionate caricature of Ray Bradbury, originally created for the Writers' Guild magazine Written By (you can read Romano's own fascinating account of the creation of this piece on his own blog, here.) The foreword is written by SF writer and futurist David Brin, who gives his appreciation of Bradbury's ability to both explore the darkness of the human heart and promote a optimistic vision of humankind's future beyond the Earth, an idea which Leiva also picks up on in one of the essays. Brin describes Leiva's book as a "personal and deeply moving tribute" which shines a loving light upon some little known aspects of this intricate and deeply passionate man".

So what of the essays contained here? They were all originally published elsewhere - some of them on Leiva's own blog This 'n' That, others in places such as Written By, KCET.org and The Huffington Post. While each one was written for a different, specific purpose, collecting them together here allows us to see a broader picture. Articles which were illuminating celebrations with Bradbury in life are now joined with items which to some extent eulogise the late author. It's great to see the pictures of Bradbury and Leiva triumphantly enjoying the dedication of Ray Bradbury Week, and quite poignant to then see the photos of the tributes a couple of years on, after Ray's passing.

The first essay, "Searching for Ray Bradbury," originally appeared in an L.A.Times blog,and attempts to give an account of what Ray Bradbury is, and where such an individual comes from. Leiva addresses what most people (think they) know about Bradbury: science fiction, and small-town America. He could have presented this essay as biography, but he chooses instead to take a Bradburyan turn and address it through metaphor:

Where did Bradbury come from? A magnificently powered nineteenth century submarine travelling 20,000 leagues; a time machine traversing centuries; a lost world where dinosaurs roam [...]Bradbury defies easy categorisation, Leiva decides, concluding that a new word will be needed in dictionaries. "What is Bradbury?" he asks. His answer: "Bradbury is Bradbury."

The second essay, "Ray Bradbury Week in Los Angeles," explains how the previous essay led directly to Leiva's creation of Ray Bradbury Week, a week-long celebration of Bradbury's life and work, timed to coincide with Bradbury's ninetieth birthday on 22 August 2010. I was fortunate enough to get to L.A. around the time of these events, and attended Ray's public birthday party, held in Glendale's wonderful Mystery & Imagination bookshop. I had to leave before the official week began, but the party gave me an opportunity to briefly meet Steven Paul Leiva, and to see him MCing the open-mic tributes to Ray which ran throughout the afternoon. The essay on Ray Bradbury Week is surprisingly brief, and in the context of the book seems unduly modest for such a grand achievement. It's not every day that a major city dedicates itself unreservedly to the celebration of an author, and I can't help feeling that it was a lot more difficult to negotiate than Leiva allows us to believe in this chapter. Nevertheless, the photos in this section speak volumes, showing us Bradbury looking sometimes proud, sometimes awed, and occasionally overwhelmed by his adopted home's expression of affection. (It occurs to me that this chapter will lose some of its power in the Kindle edition, where the pictures have been removed.)

|

| Ray's 90th Birthday Cake: a burning book |

Essay three, "London to Los Angeles, Dickens to Bradbury: a Tale of Two Signs" sees Leiva on his first naive visit to London, literally stumbling in the dark as he tries to make sense of his new surroundings, and serendipitously spotting a sign linking a church to a Dickens novel. In parallel to this, he writes of driving around Venice, California, in search of the houses Bradbury had lived in when he first moved to the West Coast. Bradbury makes a brief appearance in this piece, a sad tale in which the old Bradbury house is demolished. Fortunately, a sign attached to the house, commemorating Bradbury's having written The Martian Chronicles there, turns up, and Leiva is the one to report this happy news to others who feared it had been lost along with the house itself. A somewhat rambling piece - how did we get from a flat in London to a demolished house in Venice, CA? - but an effortless one which begins to fulfill the book's title Searching for Ray Bradbury and in the process begins to reveal just a little of Leiva's background.

The third essay also introduces Jon Eller, the co-founder of the Center for Ray Bradbury Studies, as a somewhat intrepid biographer, and essay number four follows directly on from this, being a review of Eller's book Becoming Ray Bradbury. It's a fine assessment of a fine book, bookended with a couple of anecdotes of Leiva's friendship with Bradbury.

My personal favourite of the essays collected here is chapter five, "Masterheart of Mars". Here Leiva explains how it was that Bradbury, that most non-technical of SF writers (if he even really was an SF writer; Leiva says he wasn't, and I tend to agree) came to be such an enormous inspiration to space scientists, to the extent that the team in charge of the Curiosity Mars rover decided to name the planetary explorer's base "Bradbury Landing" in 2012. Leiva puts it down to Bradbury's almost instinctive address of three aspects of the human condition which led him to advocate moving our species out to the planets, starting at Mars: we have an urge to survive, we have an urge to seek knowledge, and we have a difficult-to-define urge to not be hemmed in. This last is something that Leiva is ambivalent about, saying it is either incredibly primitive, or incredibly advanced. The resolution to that particular conundrum is probably to be found in Leiva's smart characterisation of Bradbury as "a romantic with a nineteenth century imagination combined with twentieth century anxieties", an assessment which successfully accounts for the yearning-yet-jaded view of humankind in The Martian Chronicles.

|

| Ray signs a poster at the Chronicling Mars conference in 2008 |

Essay six is a brief account of the creation of Ray Bradbury Square, a public space at Fifth and Flower in Los Angeles, right outside the public library that meant so much to Bradbury. Essay seven then continues the story with a detailed account of the dedication ceremony. As with the declaration of "Ray Bradbury Week" there is a sense of celebration, but this time with the tinge of sadness that Bradbury was not around to see the simple legend "Author - Angeleno" beneath his name.

|

| Signage at Ray Bradbury Square, Los Angeles |

Finally, essay eight tackles the title of the volume, and searches for the real Ray Bradbury. Here Leiva goes into the greatest detail about his own personal connection to Bradbury, which dates back to work they did together on a film adaptation of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland. Leiva points to a transition which had somehow occurred in Bradbury's career, where he slipped from being "just" an author with the near anonymity that so often accompanies authorship, to being a sought-after interviewee, public speaker and raconteur. Leiva almost suggests embarrassment at having, for a time, fallen into just seeing Ray as the the public persona. The essay shows how he re-connected with Bradbury the author through directing a staged reading of "The Better Part of Wisdom" in 2010.

|

| Bradbury as public speaker |

Searching for Ray Bradbury is a brisk read, partly because it is a slim volume, but also because of Leiva's essay-writing skill. Because of his initiation of so many Bradbury tributes, there is a danger that this collection could place Leiva at the centre of events, and inadvertently become self-aggrandising. But what lifts the book above this is precisely the way he finds the object of his search: hidden in plain sight, right there in Bradbury the public persona, is Bradbury the humanitarian, Bradbury the author. Leiva finds the true Bradbury by connecting anew with Bradbury's text.

|

| Steven Paul Leiva at Mystery & Imagination bookshop in 2010 |

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Halloween...

Halloween. Bradbury season. A good time of year to (re-)read Something Wicked This Way Comes, The Halloween Tree and The October Country...

And a good time to receive the news from award-winning radio dramatist Brian Sibley: that he has been commissioned to write a radio dramatisation of Bradbury's The Illustrated Man. It is to be part of a short season for BBC Radio which will also include an adaptation of The Martian Chronicles (written by someone other than Sibley). Brian has considerable experience of working with Bradbury material, having adapted a number of short stories for the series Ray Bradbury's Tales of the Bizarre. A few years ago he was trying hard to get a production of Something Wicked This Way Comes onto the air, but the BBC wouldn't bite. (Shortly afterwards, they did stage a production, but not the Sibley version.)

For Halloween, Brian has also posted something seasonal on his own blog: Death and the Magician is about the life (and afterlife?) of Harry Houdini. Brian, of course, is a connoisseur of magic, and Chairman of the Magic Circle.

Halloween is also a good time to (re-)listen to Colonial Radio Theatre's productions of Something Wicked This Way Comes and The Halloween Tree...

And a good time to reconsider the classic Orson Welles radio dramatisation of The War of the Worlds, now seventy-five years old.

It so happens that Colonial have recently produced their own audio version of H.G.Wells' novel, and in traditional Colonial style they have "done the book". No updating of the story, no attempt to relocate the events of the story to a different country, no attempt to reflect current world or political situations - just The War of the Worlds as H.G. wrote it.

It so happens that Colonial have recently produced their own audio version of H.G.Wells' novel, and in traditional Colonial style they have "done the book". No updating of the story, no attempt to relocate the events of the story to a different country, no attempt to reflect current world or political situations - just The War of the Worlds as H.G. wrote it.

This is something I have always wanted the visual media to do. Although we occasionally see an updating of Shakespeare, for the most part film and TV adaptations of classic literature will attempt to recreate the period in which a work was created, the world in which the story is set. Dickens and Austen are always set in the nineteenth century, so why not adaptations of Wells? George Pal's The Time Machine starts and ends in Victorian London, I suppose, although most of the action is in the far future. There was also a 1980s BBC TV dramatisation of The Invisible Man which was staged as a period piece. But every time The War of the Worlds is done, the aim seems to be be to recreate the effect of Wells' work - to scare the audience by showing a realistic threat - rather than to recreate Wells' actual plotting and staging. This latter is exactly what the Colonial Players have done, in audio.

Jerry Robbins' production, starring British actor David Ault, takes us back to Wells' text, but not without some creative interpolations. Wells advances his story mainly through a first-person narrator, but the Colonial Players turn much of this into dialogue, especially in the early scenes. This has led to some smart decisions, such as the presentation of Pearson, the central character, as a man who is slowly acquiring knowledge about the Martian invasion. Whereas Wells' narrator tends to sound authoritative - think Richard Burton's classic reading in Jeff Wayne's musical version of War of the Worlds - this Pearson seems to be talking off the cuff at the start, as he recalls the events he has just witnessed. By the end, with the Martians defeated, he reads confidently as he attempts to shake listeners from complacency.

Because M.J. Elliott's script follows the book, the geographical wanderings of Pearson are preserved, giving it a distinct air of authenticity, at least for a Brit like me who has some familiarity with the places named, but the casual dropping of place names with logical consistency should also make it seem authentic to anyone who is not aware of the real places. If you want to get a sense of the very real geography that Wells uses, take a look at this website, which provides maps and photos of some of the key locations.

Somehow, Robbins has managed to collapse the reading time of the novel right down. I have some audiobook versions of The War of the Worlds which give a straight undramatised reading, and they run to about seven hours. This Colonial dramatisation lasts just under two hours, and yet doesn't seem to have cut very much from the story. I put it down to some efficient dramatisation, and removal of some of the more formal sections of Wells' narration. What remains tends to be dramatic material that keeps the story moving forward.

As is so often the case with Colonial productions, the cinematic soundscapes make a strong impression. I was particularly taken with the thumping, piston-like stride of the Martian tripods, and their bellowing, almost subsonic communication. Although it's science fiction, Wells' novel works by being realistic: his Martian war machines are extrapolations of the massive mechanical contraptions which were beginning to appear in real warfare at the turn of the twentieth century, and which within twenty years would bring about the devastation of the First World War. Colonial's sound effects build upon that same kind of technology. When the first cylinders descend, they sound like missiles, weapons of war, rather than Hollywood flying saucers. There is only a modest use of cliche science-fictional sounds, and reliance more on hisses, grindings, thumps and explosions. The best soundscape comes in the scene where Pearson, in the river, goes underwater to hide or escape from the Martians. But the "call to feed", with blood-curdling screams accompanying the bellow of the Martians is quite effective - and quite appropriate for Halloween listening...

I can't finish this brief review without addressing the question of voices and accents. Brits don't sound Americans, and Americans don't sound British, so some very embarrassing results can arise in productions like this (Colonial Radio Theatre records in Boston, MA). Fortunately, with David Ault at the centre, it is very convincingly British. The secondary characters blend in well, with Joseph Zamparelli's Ogilvy and J.T.Turner's Reverend holding up well.

There's a lot to be said for the Orson Welles eve-of-Second World War version of The War of the Worlds, and even Spielberg's post 9/11 film version from 2005. It's great that Wells' story, anticipating world war and the end of empire, can find modern resonance in updated, relocated renderings of his story. But the genius of Wells was the building of the real and the mundane into an only slightly extrapolated fantasy, and it is this War of the Worlds which Colonial delivers.

If you want to treat yourself to The War of the Worlds this Halloween, you can get it as a download from Amazon or Amazon UK. And you can even get the script for Kindle!

The War of the Worlds, adapted by M.J.Elliott, directed by Jerry Robbins. 104 minutes.

Cast: RICHARD PEARSON: David Ault, CATHERINE PEARSON: Shana Dirik, PROFESSOR OGILVY: Joseph Zamparelli, WARRICK PEARSON: Robin Gabrielli, MRS WAYNE: Jackie Coco, PORTER: Seth Adam Sher, ESSEX: Fred Robbins, LIEUTENANT: Mark Thurner, REVEREND: J.T. Turner, MRS ELPHINSTONE (MRS E): Shana Dirik, CAPTAIN: Dan Powell, ONLOOKER 1 (MALE): Fred Robbins, ONLOOKER 2 (FEMALE): Shana Dirik, LONDONER 1: Mark Thurner, LONDONER 2: Jackie Coco.

And a good time to receive the news from award-winning radio dramatist Brian Sibley: that he has been commissioned to write a radio dramatisation of Bradbury's The Illustrated Man. It is to be part of a short season for BBC Radio which will also include an adaptation of The Martian Chronicles (written by someone other than Sibley). Brian has considerable experience of working with Bradbury material, having adapted a number of short stories for the series Ray Bradbury's Tales of the Bizarre. A few years ago he was trying hard to get a production of Something Wicked This Way Comes onto the air, but the BBC wouldn't bite. (Shortly afterwards, they did stage a production, but not the Sibley version.)

For Halloween, Brian has also posted something seasonal on his own blog: Death and the Magician is about the life (and afterlife?) of Harry Houdini. Brian, of course, is a connoisseur of magic, and Chairman of the Magic Circle.

Halloween is also a good time to (re-)listen to Colonial Radio Theatre's productions of Something Wicked This Way Comes and The Halloween Tree...

And a good time to reconsider the classic Orson Welles radio dramatisation of The War of the Worlds, now seventy-five years old.

It so happens that Colonial have recently produced their own audio version of H.G.Wells' novel, and in traditional Colonial style they have "done the book". No updating of the story, no attempt to relocate the events of the story to a different country, no attempt to reflect current world or political situations - just The War of the Worlds as H.G. wrote it.

It so happens that Colonial have recently produced their own audio version of H.G.Wells' novel, and in traditional Colonial style they have "done the book". No updating of the story, no attempt to relocate the events of the story to a different country, no attempt to reflect current world or political situations - just The War of the Worlds as H.G. wrote it.This is something I have always wanted the visual media to do. Although we occasionally see an updating of Shakespeare, for the most part film and TV adaptations of classic literature will attempt to recreate the period in which a work was created, the world in which the story is set. Dickens and Austen are always set in the nineteenth century, so why not adaptations of Wells? George Pal's The Time Machine starts and ends in Victorian London, I suppose, although most of the action is in the far future. There was also a 1980s BBC TV dramatisation of The Invisible Man which was staged as a period piece. But every time The War of the Worlds is done, the aim seems to be be to recreate the effect of Wells' work - to scare the audience by showing a realistic threat - rather than to recreate Wells' actual plotting and staging. This latter is exactly what the Colonial Players have done, in audio.

Jerry Robbins' production, starring British actor David Ault, takes us back to Wells' text, but not without some creative interpolations. Wells advances his story mainly through a first-person narrator, but the Colonial Players turn much of this into dialogue, especially in the early scenes. This has led to some smart decisions, such as the presentation of Pearson, the central character, as a man who is slowly acquiring knowledge about the Martian invasion. Whereas Wells' narrator tends to sound authoritative - think Richard Burton's classic reading in Jeff Wayne's musical version of War of the Worlds - this Pearson seems to be talking off the cuff at the start, as he recalls the events he has just witnessed. By the end, with the Martians defeated, he reads confidently as he attempts to shake listeners from complacency.

Because M.J. Elliott's script follows the book, the geographical wanderings of Pearson are preserved, giving it a distinct air of authenticity, at least for a Brit like me who has some familiarity with the places named, but the casual dropping of place names with logical consistency should also make it seem authentic to anyone who is not aware of the real places. If you want to get a sense of the very real geography that Wells uses, take a look at this website, which provides maps and photos of some of the key locations.

Somehow, Robbins has managed to collapse the reading time of the novel right down. I have some audiobook versions of The War of the Worlds which give a straight undramatised reading, and they run to about seven hours. This Colonial dramatisation lasts just under two hours, and yet doesn't seem to have cut very much from the story. I put it down to some efficient dramatisation, and removal of some of the more formal sections of Wells' narration. What remains tends to be dramatic material that keeps the story moving forward.

As is so often the case with Colonial productions, the cinematic soundscapes make a strong impression. I was particularly taken with the thumping, piston-like stride of the Martian tripods, and their bellowing, almost subsonic communication. Although it's science fiction, Wells' novel works by being realistic: his Martian war machines are extrapolations of the massive mechanical contraptions which were beginning to appear in real warfare at the turn of the twentieth century, and which within twenty years would bring about the devastation of the First World War. Colonial's sound effects build upon that same kind of technology. When the first cylinders descend, they sound like missiles, weapons of war, rather than Hollywood flying saucers. There is only a modest use of cliche science-fictional sounds, and reliance more on hisses, grindings, thumps and explosions. The best soundscape comes in the scene where Pearson, in the river, goes underwater to hide or escape from the Martians. But the "call to feed", with blood-curdling screams accompanying the bellow of the Martians is quite effective - and quite appropriate for Halloween listening...

I can't finish this brief review without addressing the question of voices and accents. Brits don't sound Americans, and Americans don't sound British, so some very embarrassing results can arise in productions like this (Colonial Radio Theatre records in Boston, MA). Fortunately, with David Ault at the centre, it is very convincingly British. The secondary characters blend in well, with Joseph Zamparelli's Ogilvy and J.T.Turner's Reverend holding up well.

There's a lot to be said for the Orson Welles eve-of-Second World War version of The War of the Worlds, and even Spielberg's post 9/11 film version from 2005. It's great that Wells' story, anticipating world war and the end of empire, can find modern resonance in updated, relocated renderings of his story. But the genius of Wells was the building of the real and the mundane into an only slightly extrapolated fantasy, and it is this War of the Worlds which Colonial delivers.

If you want to treat yourself to The War of the Worlds this Halloween, you can get it as a download from Amazon or Amazon UK. And you can even get the script for Kindle!

The War of the Worlds, adapted by M.J.Elliott, directed by Jerry Robbins. 104 minutes.

Cast: RICHARD PEARSON: David Ault, CATHERINE PEARSON: Shana Dirik, PROFESSOR OGILVY: Joseph Zamparelli, WARRICK PEARSON: Robin Gabrielli, MRS WAYNE: Jackie Coco, PORTER: Seth Adam Sher, ESSEX: Fred Robbins, LIEUTENANT: Mark Thurner, REVEREND: J.T. Turner, MRS ELPHINSTONE (MRS E): Shana Dirik, CAPTAIN: Dan Powell, ONLOOKER 1 (MALE): Fred Robbins, ONLOOKER 2 (FEMALE): Shana Dirik, LONDONER 1: Mark Thurner, LONDONER 2: Jackie Coco.

Friday, October 25, 2013

Ray Bradbury, Realist

A couple of days ago, David Barnett blogged for The Guardian about Ray Bradbury's non-SF, non-fantasy writing. It's a good piece, picking out a couple of examples from Bradbury's Irish and Mexican stories, and I'm sure the average Guardian reader would be slightly surprised to find that the famous American "sci-fi guy" was interested in non-fantastical tales.

I've never sat and counted, but I suspect that Bradbury's short fiction deals with "the real" at least half the time. It's certainly true that his interest in genres tended to come in waves: first the weird fiction that got him started in Weird Tales, then the detective stories that he ultimately gave up on (most of which are collected in A Memory of Murder), then science fiction (the stories that became The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451). Then, after the Moby Dick experience, the Irish stories and other "realist" works. However, even among his early works there are realist stories like "I See You Never" and "The Meadow".

Except... while I see the "real" in Bradbury, it's nearly always presented in an unreal way. The Irish stories are not real in any journalistic sense: the characters are exaggerated for comedic effect, or are caricatures of real types that he had met, or are in situations which are enlarged into a tall tale. Other of his "realist" stories from his later career have a dreamlike tone to them - as I've pointed out before, a remarkable number of stories in Bradbury Stories: 100 of his most celebrated tales begin with the narrator waking up, being awoken, or being interrupted.

Nevertheless, for all of the unreality of "The Beggar on O'Connell Bridge" (for example), the story is light-years from being science fiction, or fantasy. In Bradbury's writing there really is a continuous spectrum that runs from complete fantasy to almost real, but most of the time he stays well away from the extreme ends and occupies a middle ground where the real is rendered fantastical, and the fantastic is made real.

'Tis October, and with the witching season soon upon us it is time for the annual Ray Bradbury Storytelling Festival. This event, now in its eighth year, is a celebration both of Bradbury and of the art of storytelling, and it takes place in Bradbury's birthplace of Waukegan, Illinois. It all begins tonight at 7.30pm in the Genesee Theatre. Details are here - and that link also takes you to a video that summarises Fahrenheit 451 in two minutes and thirty-five seconds!

I've never sat and counted, but I suspect that Bradbury's short fiction deals with "the real" at least half the time. It's certainly true that his interest in genres tended to come in waves: first the weird fiction that got him started in Weird Tales, then the detective stories that he ultimately gave up on (most of which are collected in A Memory of Murder), then science fiction (the stories that became The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451). Then, after the Moby Dick experience, the Irish stories and other "realist" works. However, even among his early works there are realist stories like "I See You Never" and "The Meadow".

Except... while I see the "real" in Bradbury, it's nearly always presented in an unreal way. The Irish stories are not real in any journalistic sense: the characters are exaggerated for comedic effect, or are caricatures of real types that he had met, or are in situations which are enlarged into a tall tale. Other of his "realist" stories from his later career have a dreamlike tone to them - as I've pointed out before, a remarkable number of stories in Bradbury Stories: 100 of his most celebrated tales begin with the narrator waking up, being awoken, or being interrupted.

Nevertheless, for all of the unreality of "The Beggar on O'Connell Bridge" (for example), the story is light-years from being science fiction, or fantasy. In Bradbury's writing there really is a continuous spectrum that runs from complete fantasy to almost real, but most of the time he stays well away from the extreme ends and occupies a middle ground where the real is rendered fantastical, and the fantastic is made real.

'Tis October, and with the witching season soon upon us it is time for the annual Ray Bradbury Storytelling Festival. This event, now in its eighth year, is a celebration both of Bradbury and of the art of storytelling, and it takes place in Bradbury's birthplace of Waukegan, Illinois. It all begins tonight at 7.30pm in the Genesee Theatre. Details are here - and that link also takes you to a video that summarises Fahrenheit 451 in two minutes and thirty-five seconds!

Saturday, October 19, 2013

It was sixty years ago today...

On this day in 1953, Ray Bradbury's book Fahrenheit 451 was published. Strictly speaking, that first edition was a collection of short stories rather than a novel, since it contained not only the title work but two other pieces of short fiction: "The Playground" and "And The Rock Cried Out". Later editions would drop the shorter pieces, allowing 451 to stand on its own.

To celebrate the sixtieth anniversary, as I have reported previously, Simon and Schuster have put out a special edition of the book with new cover art - and with lots of new critical back matter compiled by Jon Eller. Here you will find Jon's account of the origins of Fahrenheit 451, contemporary reviews, and comments on the work from various notables from the book's sixty-year existence. The book also has a new introduction by Neil Gaiman.

Watch out for the remarkably short-sighted lack of promotion from S&S, though. Even their website makes no mention of the substantial content added to this edition, and they didn't even bother giving it a new ISBN number!

To celebrate the sixtieth anniversary, as I have reported previously, Simon and Schuster have put out a special edition of the book with new cover art - and with lots of new critical back matter compiled by Jon Eller. Here you will find Jon's account of the origins of Fahrenheit 451, contemporary reviews, and comments on the work from various notables from the book's sixty-year existence. The book also has a new introduction by Neil Gaiman.

Watch out for the remarkably short-sighted lack of promotion from S&S, though. Even their website makes no mention of the substantial content added to this edition, and they didn't even bother giving it a new ISBN number!

Monday, October 07, 2013

Orbiting Ray Bradbury's Mars

Just released from McFarland is a new book of essays on Ray Bradbury's work. Orbiting Ray Bradbury's Mars, edited by Gloria McMillan, started out with the intention of re-assessing Bradbury as an author with strong Arizona connections, but the book has turned out to have a broader scope.

The essays cover various topic areas: some are biographical, some scientific, some anthopological, some literary. Of particular interest to me are a couple of chapters that deal with the TV adaptation of The Martian Chronicles. Although this is one of the weaker adaptations of Bradbury, it remains one of the best known, and therefore needs some critical scrutiny.

I haven't yet read the book - I only discovered this week that it was actually available via Amazon, much earlier than had originally been advertised. I may write a longer review later, if I find time. On the face of it, though, it's a useful and up-to-date collection of essays. Contributing authors include Jon Eller, Marleen Barr and Grace Dillon. The full table of contents is on the publisher's page, here.

The essays cover various topic areas: some are biographical, some scientific, some anthopological, some literary. Of particular interest to me are a couple of chapters that deal with the TV adaptation of The Martian Chronicles. Although this is one of the weaker adaptations of Bradbury, it remains one of the best known, and therefore needs some critical scrutiny.

I haven't yet read the book - I only discovered this week that it was actually available via Amazon, much earlier than had originally been advertised. I may write a longer review later, if I find time. On the face of it, though, it's a useful and up-to-date collection of essays. Contributing authors include Jon Eller, Marleen Barr and Grace Dillon. The full table of contents is on the publisher's page, here.

Friday, October 04, 2013

Blink and you'll miss it

The Simpsons' 24th "Treehouse of Terror" episode - due to premiere this weekend - has an elaborate re-make of the entire Simpsons title sequence. I lost count of the number of familiar SF/fantasy genre references. There's a Bradbury reference in there, but if you blink you may miss it... so here it is, frozen for your extended enjoyment.

Here we see Ray inking up the Illustrated Man. And who's that looking over his shoulder? Richard Matheson?

And now, the full sequence:

Monday, September 30, 2013

Ray Bradbury Library Dedication

Last Monday saw the dedication of the Los Angeles Palms-Rancho Park Library in honour of Ray Bradbury. In attendance for the event were Steven Paul Leiva, three of Ray's daughters (Susan, Bettina and Ramona), Harlan Ellison and George Clayton Johnson.

Also present were many friends and fans of Bradbury (and Harlan and George) with their many cameras, making this one of the best-documented of Bradbury events. I was not present myself (my excuse being that I live on a different continent...) but John King Tarpinian provides a full account of the day at File 770.

After the formal dedication, Leiva, Ellison and Johnson held a discussion of their memories of Bradbury. Steven spoke of his professional relationship with Ray, which began with their work on the abortive attempt to make a film of Winsor McCay's Little Nemo (a film was eventually made, but without Bradbury's screenplay). Harlan spoke of how he and Ray would argue good-naturedly over their entirely opposing view of how the world is. George spoke of how he was always in awe of Ray's talent and generosity.

The whole discussion is preserved on video, on Harlan's Youtube Channel and also in this recording from Daniel Lambert. Although the Lambert version has a shorter running time, it does include a few additional minutes at the end of the panel which are omitted from the Harlan Channel version.

Library poster for the event

Harlan with a school group before the discussion panel

The panel discussion was held in a room which had already been dedicated to Bradbury some years ago

The panel discussion was held in a room which had already been dedicated to Bradbury some years ago

Harlan demonstrates the correct way to sign one's books - after hilariously describing Bradbury's insistence on using a thick marker pen for his book signings

Thursday, September 12, 2013

New Book about FAHRENHEIT 451 - table of contents

I've been commissioned to write a chapter for the forthcoming Salem Press volume about Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451.

The book, edited by Rafeeq McGiveron, is part of Salem's extensive Critical Insights series, which encompasses book-length studies of major authors and major novels. The books are a little bit pricey for the average reader, but are aimed primarily at colleges, schools and libraries.

The contents of the Fahrenheit 451 volume are still tentative, but Rafeeq is aiming to include chapters by the following scholars:

The book is due for release (somewhat optimistically in my view, but we'll see!) in November. The publisher's official page is here, and more detail of the proposed chapter titles are on Rafeeq's personal website here.

The book, edited by Rafeeq McGiveron, is part of Salem's extensive Critical Insights series, which encompasses book-length studies of major authors and major novels. The books are a little bit pricey for the average reader, but are aimed primarily at colleges, schools and libraries.

The contents of the Fahrenheit 451 volume are still tentative, but Rafeeq is aiming to include chapters by the following scholars:

- Garyn Roberts

- Robin Anne Reid (author of Ray Bradbury: a Critical Companion)

- Rafeeq McGiveron

- Joseph M. Sommers

- Timothy E. Kelley

- Jonathan R. Eller (co-author of Ray Bradbury: the Life of Fiction; author of Becoming Ray Bradbury)

- Anna McHugh

- Andrea Krafft

- Adam T. Bogar

- Aaron Barlow

- Phil Nichols

- Guido Laino

- Wolf Forrest

- Imola Bulgozdi

The book is due for release (somewhat optimistically in my view, but we'll see!) in November. The publisher's official page is here, and more detail of the proposed chapter titles are on Rafeeq's personal website here.

Monday, September 09, 2013

New Book: SF Across Media

At long last, we have a publication date for a book containing one of my

essays. Science Fiction Across Media: Adaptation/Novelization is due out

on 16th September 2013. The book originated in the 2009 conference of the same name, which was held at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

My chapter is about Ray Bradbury's short story "A Sound of Thunder" and the ways it has been treated in difference media adaptations. I wrote it so long ago that I can barely remember what it's about (and so long ago that I will probably cringe at some of the things I say in it). I do recall that I refer to the story; to Bradbury's own TV dramatisation of the story; to Peter Hyams' disappointing film expansion of the story; and to several illustrators' treatment of the story's imagery.

Interestingly, the book's editors (Thomas Van Parys and I.Q.Hunter) or publishers (Gylphi Press) have chosen to use another Bradbury adaptation to illustrate the cover: Fahrenheit 451. It shows Cyril Cusack as Fire Chief Beatty warming his hands over some burning books while Oskar Werner looks on.

My chapter is about Ray Bradbury's short story "A Sound of Thunder" and the ways it has been treated in difference media adaptations. I wrote it so long ago that I can barely remember what it's about (and so long ago that I will probably cringe at some of the things I say in it). I do recall that I refer to the story; to Bradbury's own TV dramatisation of the story; to Peter Hyams' disappointing film expansion of the story; and to several illustrators' treatment of the story's imagery.

Interestingly, the book's editors (Thomas Van Parys and I.Q.Hunter) or publishers (Gylphi Press) have chosen to use another Bradbury adaptation to illustrate the cover: Fahrenheit 451. It shows Cyril Cusack as Fire Chief Beatty warming his hands over some burning books while Oskar Werner looks on.

Wednesday, September 04, 2013

Tuesday, September 03, 2013

Frederik Pohl (1919-2013)

I just heard that Fred Pohl has passed away. He was a major figure in twentieth-century American SF, as editor, agent, novelist and short-story writer. He edited pulp-magazines before the Second World War, rubbing shoulders with other founding figures of the genre as we know it today. He wrote satirical novels and short stories in collaboration with C.M. Kornbluth in the 1950s. He edited Galaxy magazine in the 1960s. In the 1970s he had what for many people would be a late-career flourish with a string of award-winning novels such as Gateway, Man Plus (probably my favourite of his works) and Jem.

But that late-career flourish in his 50s turned out to be mid-career, as he continued working right through to his 90s. His authobiography, The Way The Future Was, consequently turns out to be a rather incomplete work as it was published in 1978 when Fred was a mere 58 years old! In recent years, he effectively extended the book by becoming a prolific blogger with his The Way The Future Blogs.

I met Fred in 2008 at the Eaton Conference in Riverside, California. He appeared on a panel with guest of honour Ray Bradbury. I had a chance to talk to him briefly about his work, telling him that I had re-read Man Plus on the flight from the UK, and found that it held up well for a thirty-year-old book. I have a few photos from the event, including one of me talking to Fred, but my favourite is this shot of him looking pensive. In the background, Larry Niven (standing) is sharing a joke with Ray Bradbury; and further back is SF scholar Eric Rabkin (seated), talking to Fred's wife Elizabeth Anne Hull.

But that late-career flourish in his 50s turned out to be mid-career, as he continued working right through to his 90s. His authobiography, The Way The Future Was, consequently turns out to be a rather incomplete work as it was published in 1978 when Fred was a mere 58 years old! In recent years, he effectively extended the book by becoming a prolific blogger with his The Way The Future Blogs.

I met Fred in 2008 at the Eaton Conference in Riverside, California. He appeared on a panel with guest of honour Ray Bradbury. I had a chance to talk to him briefly about his work, telling him that I had re-read Man Plus on the flight from the UK, and found that it held up well for a thirty-year-old book. I have a few photos from the event, including one of me talking to Fred, but my favourite is this shot of him looking pensive. In the background, Larry Niven (standing) is sharing a joke with Ray Bradbury; and further back is SF scholar Eric Rabkin (seated), talking to Fred's wife Elizabeth Anne Hull.

Monday, August 26, 2013

James Gunn

One of the delights of this year's Eaton Conference in Riverside, California, was the opportunity to meet the incredible James Gunn.

(Pictured at the James Gunn panel are (from left to right) Nathaniel Williams, Michael Page, James Gunn, Chris McKitterick.)

What's so incredible about James Gunn? For starters, he's ninety years old this year, but could easily pass for twenty years younger. More importantly, though, he is what one conference speaker called "a triple threat": not only a successful author of science fiction, but a successful teacher of SF and creative writing, and a successful critic and historian of SF.

While other significant genre figures were associated with the Eaton Conference because they were to receive awards - Ray Harryhausen, Stan Lee and Ursula Le Guin all received Eaton Awards this year - Gunn was present because there was going to be a panel discussing the three strands of his career. The panel was part academic study, part reminiscence from those who have worked with Jim , and all celebration of his life and work. (The panel organisers told me they were inspired to do this by the Ray Bradbury tribute events I organised for last year's SFRA conference in Detroit.)